Recruiters in 3D animation move fast. They open a reel, watch the first ten seconds, and decide if they keep going. They look at your email, your ArtStation link, and the way you label files. In that short window, they answer a quiet question: Can this person solve real production problems, or are they still stuck in school projects?

For many recent grads, that moment feels unfair. You spent years learning software, finishing assignments, and racing against deadlines. You might even do my essay for me with native authors during exam season. In the job hunt, though, nobody can step in and organise your portfolio for you. The way you present your work is part of the work.

The good news is that recruiters tend to want the same core things. Once you understand their checklist, you can build a portfolio that speaks their language instead of shouting in the dark.

The Reel Comes First, But Context Matter

Almost every recruiter starts with the showreel. They want something short, focused, and honest. One to two minutes is often enough. If you have less great work, a shorter reel beats a long one padded with weak shots.

They look for clear structure: the strongest works at the beginning, nothing experimental at the end that feels unfinished. Add a simple title card with your name, speciality, and contact details. Avoid an elaborate intro sequence that burns the first twenty seconds.

Context matters as much as the images themselves. If you animated a character in a group project, say so. If you handled layout and camera as well as performance, mention that in a caption or in the video description. Recruiters try to read what you actually did, not just what appears on screen.

Showing Craft, Not Just Software

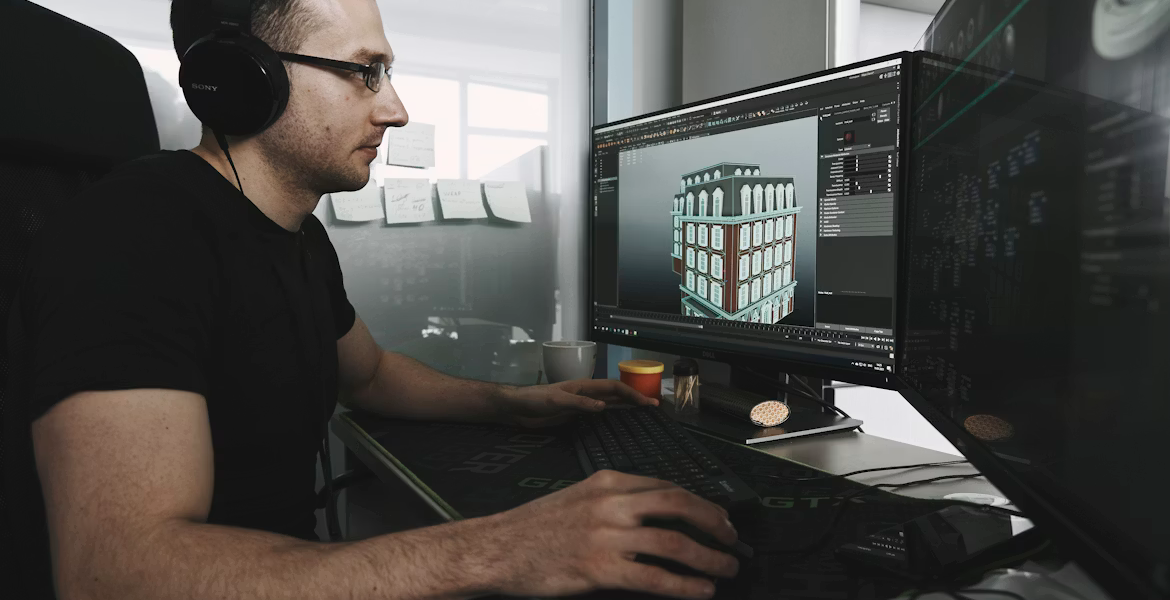

Studios care less about how many tools you list and more about how you use them. Anyone can install Blender or Maya. Fewer people can give a character a believable weight as they sit on a chair or turn their head.

This is where fundamentals carry you. Timing, spacing, arcs, anticipation, follow-through, appeal. These principles show up even in simple exercises. A polished bouncing ball with convincing weight says more about your potential than a cluttered scene that looks impressive at a glance but feels wrong in motion.

You cannot fake that with shortcuts. An animator may experiment with an essay generator for a theory class, yet there is no equivalent in production. Recruiters watch for shots that feel earned. They look for work that hints at hours spent on reference, blocking, polish, and feedback.

How to Explain Your Process Like a Professional

Increasingly, recruiters expect some form of breakdown. They want to know how you think, not only what you render. This can be a separate PDF, a page on your site, or even text under each reel shot.

For each key piece, you can cover a few points:

- What the brief or assignment asked for

- Which specific responsibilities you had

- Which tools and rigs you used

- What problem you had to solve and how you approached it

Treat this like production notes, not a diary. Clear, neutral language works best. You do not need fancy phrases. You need enough detail for someone skimming during a busy hiring sprint.

Thinking this way is similar to how an essay writer structures an argument. There is an opening idea, supporting points, and a conclusion that shows what changed. In animation, the "conclusion" might be a side-by-side of reference and final shot or a short note on what you would improve if you had more time.

Portfolios That Show Range Without Losing Focus

Beyond the reel, recruiters will click into your stills, playblasts, and personal projects. They look for consistency. Even if styles and tones differ, they want to see the same care for posing, silhouette, and clarity.

A focused portfolio for a 3D animator usually includes:

- A main reel

- A few shots broken down with notes or process images

- Still frames that show strong posing and staging

- Very limited non-animation work, only if it supports your main goal

This is where you decide how much range to show. One path is to highlight a specific lane, such as character animation for games or creature work for film. Another is to present a slightly broader set of shots that still connect. Recruiters do not expect a recent grad to have a perfect niche, but they do appreciate a sense of direction.

Using References, Examples, and Feedback

Using References, Examples, and Feedback

Good animators copy in smart ways. They study films, games, and other reels to understand why certain choices work. They look at breakdowns from senior artists and then try similar exercises on their own.

You might treat a professional shot the way you once treated an essay example for a tough class. Not as something to mimic line by line, but as a model for structure and intention. What is the character's goal? How do timing and spacing support the emotion? Which frames carry most of the weight?

Feedback plays a huge role here. Recruiters pay attention when you show that your shot has improved through critique. Simple captions such as "second pass after notes on readability" signal that you can listen and iterate. In production, that mindset matters as much as raw talent.

Professional Habits That Signal You Are Ready

By the time someone opens your application, they may have already reviewed dozens that week. Annie Lambert, who works with EssayPro, an essay writing service, says that small professional habits send a quiet signal that you will be easier to work with than most.

Recruiters notice:

- File naming and version control that look organised

- Short, clear emails with links that work on the first click

- Profiles that match across platforms, with the same name and focus

- A CV that highlights relevant projects instead of every side job

These details take time. They also make life easier for the people reviewing your work. Many grads focus only on visuals and treat everything else as an afterthought. The applicants who align both tend to move forward.

Final Thoughts

Breaking into 3D animation takes time. You send reels, hear nothing back, and start questioning every shot. A clear sense of what recruiters value turns that fog into something closer to a map. They look for solid craft and proof that you can finish work. Each reel, each revision, each email slowly shapes a body of work that begins to feel ready for the studio floor. In time, studios notice.